How Many Tv Cameras Were Used At A Mlb Game In1970

This story appears in the October. 26, 2015, event of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

A waning gibbous moon hung similar a medallion over Charlestown, N.H., on the first clear dark after a three-day nor'easter. A light current of air rustled the lindens and oaks along Main Street. The bells of St. Luke's Episcopal Church suddenly began clanging at the strange hour of i:07 a.grand. Such an intrusion on the dead of night alarmed the local police. No services could possibly be held in these commencement hours of Wed, Oct. 22, 1975.

The corner of Main and Church, whence the bells tolled, is 128 miles from Fenway Park, 170 miles from Cooperstown, N.Y., and as near to the roots of America as anyplace else—which is to say its story actually begins in England. A struggling young cabinetmaker named Richard Upjohn left that country for the U.S. and an architectural career effectually 1829. His big interruption came 10 years later, when he was hired to pattern and build a new Trinity Church in New York Urban center. He delivered what still stands as one of this land's foremost monuments to Gothic architecture.

Upjohn became an American master of the Gothic Revival style and gained wide influence for his 1852 publication Rural Architecture, which provided the designs for small congregations to build churches all over the state. St. Luke'south, built over five months in 1863, is Upjohn's only wooden church in New Hampshire: a uncomplicated, sturdy, white building shaped like a cross, with pointed biconvex blood-red doorways; a slate-shingled, steeply pitched roof; and a two-story tower with almond-shaped louvered openings on 4 sides, the better to allow the bells' ringing to carry over the Connecticut River Valley.

Those bells. They would not stop. By Godfrey if any of the iv,300 residents of Charlestown could sleep through that racket. A police officer rushed to the church and climbed to the tower. There he establish a Charlestown resident, David Conant, 61.

"What are y'all doing?" the officer demanded.

"Carlton Fisk just hitting a dwelling run to win the Globe Series game tonight for the Ruby-red Sox!" Conant announced.

Fisk was born across the river in Bellows Falls, Vt., and raised in Charlestown. Conant's married woman used to modify Fisk'south diapers. Conant's son played baseball with Fisk at Charlestown High. The broad-shouldered, square-jawed Fisk was as much a testament to New England values as St. Luke'south itself. As he once told the Concord Monitor, "My cadre was anchored in New Hampshire. Being stubborn and unwavering, never giving in, never giving up, no matter what the obstacles."

Everybody in Charlestown knew Fisk, the kid who was chosen Pudge ever since he weighed 105 pounds as an eight-year-sometime. Now the constabulary officer understood what all the commotion was almost. "Hell," he replied, "if I had known that, I would accept come and helped you."

Conant rang the bells for four minutes. Quiet finally returned to Charlestown at 1:xi a.m., simply the resonance of the bells of St. Luke's volition never cease.

That nighttime endures non simply because a son of New England hitting one of the about famous home runs in baseball game history, the ascendancy that concluded Game half-dozen and fabricated necessary an almost-equally-thrilling Game seven to confirm a pinnacle Reds ball guild as world champions. That night also changed American culture.

Forty years subsequently our arenas and ballparks and especially our living rooms, dens, man caves, bars, restaurants and every other identify nosotros assemble to picket sports take become our secular versions of St. Luke'southward. Worship is non too stiff a discussion to describe what nosotros practice at the nexus of our ii favorite pastimes: sports and goggle box.

Think about what we now take for granted in televised sports. Prime number-fourth dimension starts, the networks influencing when games are played, cameras placed at unusual vantage points, reaction shots of athletes away from the brawl—all of it can be traced to the NBC telecast of Game six of the 1975 World Series. What the 1958 NFL championship game did for pro football game, Game half-dozen did for televised sports. In that location is merely before and after. It is the most influential telecast in the 76 years that baseball has been televised.

"The sixth game was one of the best ever played," William Leggett wrote in SI and then, "and NBC rose to the occasion with perhaps the best baseball game telecast e'er put on the air."

In retrospect, information technology was easier to build St. Luke'due south than it was to make that 4-hour event. Information technology took much more than Fisk's home run to change televised sports forever. Information technology took the conflation of happy accidents and huge personalities, including rain, money, Bowie Kuhn, Red Smith, Howard Cosell, rain, O.J. Simpson, Pete Rose, Sparky Anderson ... and more pelting. Oh, did information technology rain.

*****

Scroll to Continue

SI Recommends

A telegram arrived at the Lenox Hotel on Boylston Street in Boston during the terminal week of the 1975 regular flavor. It was addressed to a guest, Dick Stockton, a 32-year-old broadcaster who was wrapping upward his outset season calling play-by-play for the Cherry-red Sox. Stockton's timing was superb. The Red Sox won 95 games, their nearly since 1949.

The telegram was a bonus for the rookie journalist. Stockton, who only 12 months earlier had been a freelancer for a Boston NBC station with no baseball experience, ripped open the envelope. He hardly could believe the typewritten words:

Nosotros are pleased to advise you of your nomination and approval to work with us during the 1975 World Serial for the telecast of the first and sixth game. $500 a game. Please do not include the color blue in your wardrobe. Adept luck. Chet Simmons, NBC Sports.

Today the telegram is framed and hanging on the wall of Stockton's Florida home.

*****

Game 6, which followed a travel day, was scheduled for Saturday afternoon, October. 18. The Reds were one victory away from the franchise's first championship in 35 years. But they would take to wait at least another twenty-four hours. The nor'easter that had brought sheets of rain to Boston on Friday night showed no signs of quitting. At 9:20 a.yard. Kuhn, the commissioner, called the game and rescheduled it for the following twenty-four hours at 1 p.chiliad.

The newspapermen, who had grown upwardly with the the World Series starting a few days after the regular flavor (with no playoffs equally a preamble) and played exclusively in daylight (the ameliorate for deadlines), blamed the postponement on television. "The whole competition could have been completed earlier now and that title decided in lovely weather if baseball game hadn't sold out its prime spectacle equally a weekend special for the TV hucksters," wrote Smith, the Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist for the The New York Times who was born in 1905, the year of the second Globe Series.

The forecast for Dominicus sounded no ameliorate, which sent the press corps into a tizzy about whether Kuhn would dare play Game 6 on a Monday night. Baseball had played its starting time Globe Series night game in 1971, and so dipped a few other toes in the h2o over the next four years by scheduling the three weekday games (3, four and 5) at dark. Game half-dozen had never been played at night. "It all boils down to the fact that baseball stupidly puts the interests of the networks and their viewers alee of the greenbacks customers' good," Smith wrote.

But Kuhn'due south choice wasn't so simple. By playing Game 6 on Mon nighttime, he would be putting baseball up against not only Monday Night Football game, in which Simpson's Buffalo Bills were playing the New York Giants, but also the tiptop-rated show on television, the sitcom All in the Family, which was pulling in a staggering 30.i rating at a time when viewers still had few choices beyond ABC, CBS and NBC. (Only 14% of homes had cablevision television.) "Relish is the incorrect word," Kuhn replied when a reporter asked if he relished such a caput-to-head-to-head matchup.

Many houses had only one television, and the networks packed prime time with shows designed to allow the unabridged family to gather around the Goggle box afterward dinner. Eight o'clock was reserved almost exclusively for dramas and sitcoms. Sports had no footing in network television at eight p.thou.; the networks and advertisers were skeptical that sports could work at that hour considering, while they might appeal to dad, they would not win the whole family's attention. ABC had been running Monday Nighttime Football game since 1970, but those games had 9 p.m. kickoffs, by the "family window" coveted by advertisers.

Baseball game tried its own Mon-night games in the early on 1970s, but the reaction from viewers was and then tepid that in '73, NBC appear that it would recruit celebrity game analysts such as Pearl Bailey, Woody Allen and Dinah Shore. I glory invited to join the NBC booth that flavour was MNF fixture Cosell, who promptly ripped baseball. "Unfortunately," he said on air, "it is impossible for us to go along to camouflage the indisputable fact that this game is lagging insufferably."

Baseball was regarded as too slow. A downturn in criminal offense, which prompted the American League to adopt the designated hitter rule in 1973, didn't help. Attendance was stagnant: Seven of the 24 teams failed to describe one million fans (fewer than 12,000 per game). Ratings for the 1974 World Series were down 20%. The flow of national TV coin showed little to no growth. In May 1971, Kuhn appear a iv-year contract with NBC that included a vii.6% increase in almanac payments, but the have for each club actually declined because the majors had expanded from 20 to 24 teams.

Four years subsequently, in March 1975, Kuhn announced that ABC would join NBC in a new deal with MLB. He proudly trumpeted a 29.3% increase in total fees as "enormous." Merely considering of inflation, the truthful value of the deal was about equal to the 1971 deal. The big Telly money the sometime pressmen similar Smith worried about wasn't in that location—not all the same, anyway.

• More MLB: Full postseason schedule, beginning times, TV listings

*****

No person created more institutional baseball memories than Harry Coyle. He directed 36 Earth Serial, all for NBC, beginning with the first the network covered, in 1947. It was through Coyle's management that nosotros saw, even if it was many years later, Lavagetto suspension Bevens's heart in '47, Mays rob Wertz in '54, Berra spring into Larsen'southward arms in '56, the ball go through Buckner'south legs in '86, Gibson take Eckersley deep in '88. Coyle gave united states of america the visual encyclopedia of postseason baseball.

It was Coyle who pioneered the use of the centerfield camera, capturing the strategic embroilment of bullpen-batter-catcher. Coyle also wrote a xiv-page manual for televising baseball that was such a definitive work that it was called Harry's Bible. It included each camera operator'due south assignment on the most common plays and the rapid progression of how those shots should be used.

Coyle, a one-time World War Two bomber pilot, was 53 in 1975. He was a cigarette-smoking, gruff-talking, dese 'n' dems kind of guy who walked in the swaying manner of John Wayne and was known to salve himself between the production trucks during commercial breaks. Such a legend did he go that the broadcaster played by Bob Uecker in the 1989 baseball game farce Major League was named Harry Doyle.

On the night of October. 21, 1975, in a parking lot behind the rightfield seats of Fenway Park, a young production assistant named Michael Weisman would accept his seat in NBC's main production truck, immediately behind Coyle. Information technology was Weisman's job to run the graphics, such equally flashing the brawl-and-strike count. "I thought, Oh, my God, I remember being ten years sometime and watching Tony Kubek get hit in the throat, and this is the man who brought me the pictures," Weisman says of Coyle. "This is the man who brought Koufax into my house in '63 and the Miracle Mets in '69. Information technology's very rare you lot could work with someone who was the best in history at what he did.

"I don't know how he did it. For all those years he was under such intense pressure. Every pitch could lead to history, and you lot can't miss one."

*****

Dominicus arrived. So did more pelting. Kuhn called the game at ix:23 a.m. And so he announced a game fourth dimension for Mon: 8:xxx p.m. "My inclination is toward a night game to ameliorate accommodate the fans," Kuhn said.

Smith was apoplectic. He eviscerated Kuhn in print again. "Exposing greenbacks customers to raw night common cold is a novel mode of accommodating them," Smith wrote. "All-around TV sponsors at prime fourth dimension is something else again." The two days of rain had washed more than just postpone the World Series; they made for a new war, between the purists who wanted to protect the agrestal-rooted game they had grown up with and the profiteers of a foundering sport who saw TV money every bit the way forward.

The Monday-dark ratings war would never happen, though. Monday morning time brought only more rain and more carping. Another Times columnist, Dave Anderson, took the baton from Smith subsequently in the week. "Nureyev isn't asked to dance on water ice, Heifetz never had to play the violin with mittens," Anderson wrote. "But for the greater glory of the Nielsen ratings, World Serial players are expected to compete in weather condition that non only is unsuitable to their skills but too would not always be condoned during the regular flavor."

Kuhn finally rescheduled the game for Tuesday at eight:30 p.m. The World Serial had been on hiatus for four days. Bitterness and fatigue saturated the printing corps as surely as the rain did. "The mood past so," Stockton says, "was, 'Let's get this affair over with.'"

*****

Tony Kubek, the former Yankees shortstop who quickly became the sharpest baseball annotator on television, would walk around a ballpark before a World Serial in the manner of a nature photographer studying the mural. Instead of a camera, he would comport a yellow legal pad and a pen. Accompanied by executive producer Scotty Connal, Kubek would expect for camera sight lines that might offer a unique perspective on the upcoming games. In 1974 at Dodger Stadium, for instance, Kubek suggested that NBC place a camera in the field boxes backside get-go base of operations with a direct view of the pitcher, shooting through the open up space between the outset baseman and the runner taking a lead. Kubek knew that the A's carried a compression-running specialist, Herb Washington. In the ninth inning of Game two, with Oakland down a run, Washington pinch-ran at commencement base. Sure enough, Dodgers bullpen Mike Marshall picked him off.

A yr later Kubek and Connal were walking the perimeter of Fenway Park when Kubek began jotting on his yellow legal pad. "Scotty, with Rose and Morgan and Griffey and Concepcion, the Reds like to run," Kubek said. "What if nosotros had a camera in the leftfield wall looking in at 2nd base? We might get some hard takeouts, some steals and slides, a lot of unusual things."

Connal was intrigued. Kubek, Connal, Coyle and Chet Simmons, an NBC Sports executive, walked across leftfield to the Light-green Monster and were happy to see in that location was a rectangular opening in the wall, similar to the vision slit in a tank, so the scoreboard operators could watch the game. They decided it would be a perfect place to put a photographic camera.

*****

At The End Of The Curse, A Approving: '04 Red Sox, Sportsmen of the Year

A beautiful dawn broke over Boston on Tuesday, Oct. 21. The forecast called for a partly sunny sky and a high temperature nearly 70°, dropping into the high 50s at night. Baseball game weather. Finally.

John Kiley headed to Fenway Park to play his Hammond 10-66 organ, a 574-pound monster made of mahogany and ebony that retailed for $ix,800. Kiley was eleven days away from turning 63, which is to say he was six months younger than Fenway Park. When he was fifteen, Kiley began playing the organ at the Benchmark Theatre in Roxbury, Mass., providing the score to the silent movies. Information technology was clear that the male child had a gift for matching music to the moment. He played other motion-picture show houses around Boston until he landed a job in 1934 as the musical managing director of WMEX, a job he held until 1956. Then one day a regular listener called and offered him a job. The listener was Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey, who hired Kiley to bring his music to Fenway.

In the eye of the 7th inning of Game 6, Kiley would pound out "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" on his X-66. The song was not yet a staple of major league ballparks. That tradition would take total root the adjacent season, when White Sox broadcaster Harry Caray led fans at Comiskey Park in singing the melody.

*****

Calling Fisk's home run on NBC gave a huge boost to the then-largely-unknown Dick Stockton.

Al Messerschmidt/Getty Images

Simmons had come up upwardly with a rotation for his World Series circulate booth that resembled how Anderson, the Reds manager known as Helm Hook, treated his pitching staff. Those taking turns at the microphones were NBC play-past-play men Short Gowdy, 56, and Joe Garagiola, 49; Kubek, forty; and local announcers Stockton and Ned Martin, 52, of Boston and Marty Brennaman, 33, of Cincinnati.

Stockton made his baseball national television debut in Game 1. Role of his task was to read promotional re-create for a show that was scheduled to debut that dark: Saturday Night Live. Stockton shared the booth with Kubek and Gowdy, the legendary broadcaster who one time chosen the Super Bowl, Earth Series and Final Four in the same year. Gowdy and Stockton each did 4 1/two innings of play-by-play, with Gowdy leading off. Every bit Gowdy turned over the duties to Stockton in the bottom of the fifth, he told viewers, "You'll enjoy listening to Dick."

Recalled Stockton, "Tell me which network top play-past-play announcer today would keep with this. Are you kidding me? He made me feel so at habitation. I'll never forget what he did."

Gowdy, though, would exist pushed out past Garagiola as NBC's lead play-by-play human the next season. Garagiola had done well as a 1975 Saturday Game of the Week guest analyst. It helped, too, that he was a spokesman for Chrysler, a major baseball game sponsor that wanted its man to play a big role in the network's baseball coverage.

Game 6 was Stockton'due south only other World Series TV consignment. This fourth dimension he would exist working with Garagiola and Kubek, the colour man. Stockton would do play-by-play for the first 4 one/2 innings, showtime with the first pitch thrown by Boston starter Luis Tiant. With a possible Reds clincher on tap, NBC wanted Garagiola in identify to telephone call the concluding out of the World Series.

Shortly before the game, in the press dining room, Stockton ran into Peter Gammons of The Boston Globe. Gammons introduced him to a young Globe reporter: "Dick, this is Lesley Visser." It wasn't long before the urbane Stockton asked her out to dinner. Visser said yep and gave him her phone number.

It would be a bong ringer of a night for Stockton equally much as for Fisk. Stockton would become an uncle that night, to a male child born to his sister during the game. He would brand the broadcasting phone call of his life. And he met his future wife. (He and Visser married in 1983 and divorced in 2010.) After the Series, Stockton took Visser to a Hungarian restaurant in Boston. Someone mentioned to Visser that it was the tertiary time that week Stockton had dined at the establishment, each time with a different young lady.

Replied Stockton, "What can I say? I like the chicken paprikash."

#http://www.120sports.com/video/v155061116/remembering-fisks-walkoff

*****

By now the events of Game half dozen are as familiar as stops on the T. How practise you lot go from Tiant to Fisk? You go through Lynn's Crash, Carbo'southward Homer, "No, No" Doyle and Evans'southward Grab. Thirty-iv players would get into the game, including 12 pitchers, viii of whom were used by Anderson.

The game reached the top of the 9th tied. It was 11:30 p.m., and 76 million people were watching the game on NBC—35% of the U.Due south. population. Simmons and producer Roy Hammerman decided to have Kubek leave the broadcast booth and caput to the Reds' clubhouse, where he would conduct interviews in the event of a clinching victory. Coyle spoke to Garagiola: "Use Stockton equally your color man."

Neither Garagiola nor Stockton would mention on air that Kubek had left the booth for the clubhouse—at to the lowest degree not until the bottom of the 11th inning. They would exercise so then only considering the NBC switchboard in New York Urban center was lighting up with phone calls from viewers who were worried that something had happened to Kubek.

When the game headed to the tenth inning, Simmons, Coyle and Hammerman had another decision to make: Who should be the play-by-play human being? There had been no contingency for actress innings. So they fabricated one up on the wing: Stockton and Garagiola would alternate innings, with Stockton up outset. It truly was his lucky night.

*****

Bottom of the 12th inning. All the same tied, 6–6. Information technology was an even-numbered inning, so it was Stockton'southward.

Kubek left the Reds' clubhouse and walked the concrete tunnel that connects the clubhouse to the visiting dugout. He saw Anderson, who had ducked into the tunnel to smoke a cigarette.

"Hey, you've been in this state of affairs before," the manager said to Kubek, who played in six Earth Series, four of which went 7 games.

"No, I haven't," Kubek said. "Not similar this."

Anderson tilted his caput toward the dugout steps. "Come on in," he said.

Kubek had one pes on the bottom pace of the Reds dugout as Fisk took the outset pitch from Pat Darcy for a ball. Kubek could hear Anderson and Reds pitching coach Larry Shepard talk. "How many pitches has he thrown, Shep?" Anderson asked.

"Twenty-eight."

"Damn. He ain't thrown that many in weeks."

The side by side affair Kubek heard was the crevice of Fisk's bat.

*****

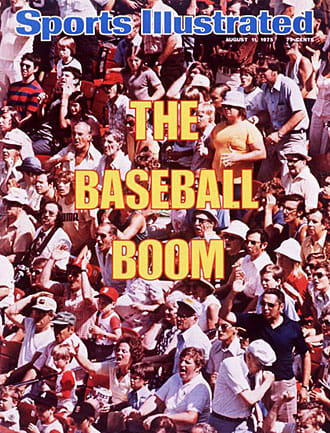

Every bit this 1975 SI encompass attests, baseball was already surging that summertime, but Game 6 catapulted the sport to even greater heights.

Neil Leifer for Sports Illustrated

Carlton Fisk was built-in two months subsequently the get-go World Series telecast, in 1947, when at that place were just nigh 100,000 television sets in the entire land. The manager of the World Serial did not own one. Coyle could non afford it. Tv set sets ran about $500. Coyle made $65 a week.

Fisk's upbringing in Charlestown may accept begun just as the television era was dawning, but it played out non as well differently from that of the townsfolk who were born in the Ceremonious War days when St. Luke'southward was built. The son of Cecil and Leona Fisk grew up in a white clapboard farmhouse. Neighborhood ball games were held in the Fisks' side one thousand. Cecil built a backstop using two wooden stakes and craven wire. The kids used cow patties for bases. The actually long dwelling runs broke windows in the house across the route. And when the games ended, Leona would be set up with a basket of freshly baked cinnamon rolls and glasses of cold milk.

This time the baseball Fisk striking wasn't traveling toward the neighbor's window. It was heading for the foul pole to a higher place the Dark-green Monster. And information technology was traveling very fast.

*****

"There information technology goes! A long drive. . . . If it stays fair. . . . Home run!"

And and then Stockton did something almost as memorable as the perfect clarity of his phone call: zero. He and Garagiola stayed silent equally Fisk rounded the bases, jumped on home plate and fell into the arms of fans and teammates. Stockton did non speak again until just before Fisk pushed his way into the Boston dugout. Finally he said, "Nosotros will have a seventh game in this 1975 Globe Series."

His tribute of silence lasted 36 seconds.

"I just did what I'yard supposed to practice," Stockton said. "There are two kinds of home runs: the drives that are deep and you lot can requite a rhapsodic call—It's way back ... it could be gone—and there are the ones like this one, and you have a nanosecond and it's going to be off-white or foul and y'all take to go it right and you don't have much time to have much flourish on the call.

"The only thing that hit me was, 'If it stays off-white....' That was the cardinal thing there. And afterward it was a dwelling run, I but wanted to shut up. I wanted to make sure I'g not going to scream and yell. It was total instinct. I didn't know whatever better or any worse. I always felt the guy who invented that technique was Vin Scully. What's improve than the audio and pictures? I wasn't aware of that technique at the time. Information technology was purely instinct."

*****

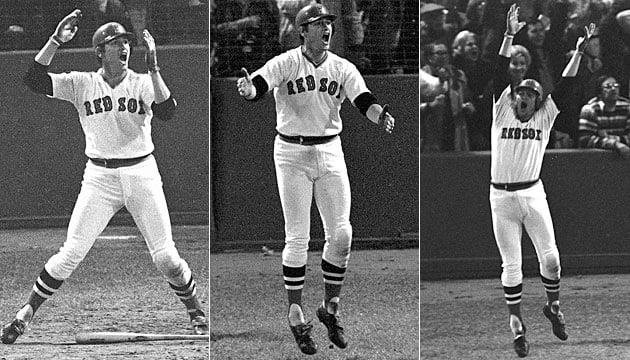

The reaction shot that captured Fisk willing the brawl off-white and jumping for joy became the game's nigh unforgettable image.

Harry Cabluck/AP (iii)

Equally Fisk dashed for dwelling, zigzagging because of the humanity in his mode, John Kiley knew just what to coax out of that monster Hammond X-66: Handel's "Hallelujah Chorus." Hearing the Ten-66 was another pearl made possible by Stockton'south 36 seconds of silence. Y'all tin can hear Kiley, as if back in the ornate silent-movie palaces of the Hub, choose the perfect sound rails as Fisk scored the last run of a long night. Later, when Fisk came back on the field to talk to Kubek and to bask in the adoration of fans who did non want to leave, Kiley bankrupt into "For He's a Jolly Skilful Fellow" and then "Give Me Some Men Who Are Stout-Hearted Men" and then "The Beer Butt Polka" and then ... well, and so anything with a practiced beat to brand the joy seem as if it could terminal forever.

*****

Inside the truck, as the home run unfolded, Coyle stuck to The Bible: centerfield shot of the pitch, cutting to the high dwelling camera to follow the flight of the ball off the foul pole and to the ground, cut to a high third-base-side camera following Fisk as he rounds offset and second, cut to a centerfield shot of the febrile fans standing and auspicious behind the Boston dugout, cut back to the high third camera as Fisk rounds third base, cut to a low first base photographic camera of the crowd and cut in time to see Fisk bound on home plate—six cuts in all.

Coyle showed his first replay ane minute after the brawl was hit. It was from the high third camera. It showed Fisk from backside, jumping afterward he knew the ball was a habitation run and then clapping his hands. Xx seconds later Coyle punched upwardly his second replay: an angle down the line, toward the leftfield wall, that showed the brawl hitting the screen fastened to the foul pole. He cut dorsum to alive pictures, i from the high home camera showing the field and another from the high third photographic camera that panned the oversupply.

Around that time Simmons was standing in the back of the product truck, on the phone with NBC New York, coordinating the "throw"—the moment when the network switched from the coverage in Boston to programming that would follow. Suddenly his optics found one of the many pocket-sized monitors in a large wall in front of Coyle, i that was off to Coyle'south side. "Wait at that!" Simmons shouted. "What is that up in that location?"

It was the feed from the photographic camera in the leftfield wall, the 1 Kubek had recommended for action at 2nd base. This camera, a ane-time placement, was non in Coyle'due south replay rotation; the feed from that camera wasn't fifty-fifty in the director'southward line of vision. Alerted by Simmons, Coyle looked up. "Oh, my God," he said. "Let's accept that."

Coyle punched up the replay from the photographic camera, which was operated past Lou Gerard. Two minutes and xi seconds had passed since Fisk hit the habitation run. Finally the world saw it: an isolation shot of Fisk as the ball was in the air. Iii times Fisk waved with his arms to his right, trying to semaphore the baseball fair. When he saw it hitting the foul pole, Fisk jumped in delight then jumped again. Coyle froze the shot on Fisk's second jump.

In the NBC studios in New York, John Filippelli, a young desk banana who was cutting highlights of the game and would later piece of work next with Coyle equally a producer, was struck by the sight of Fisk. "Wow, that's the shot you recall," Filippelli said. "It goes back to an adage I used many times: The way you document a game is well-nigh as important as the game itself."

"It was arguably i of the greatest replays of all time," Weisman said. Thirty-iv years later, speaking to author Mark Frost for his exquisite 2009 volume, Game Half-dozen, Weisman revealed that it was Simmons, not Coyle, who deserved credit for noticing the Fisk reaction shot. Just before doing so, Weisman spoke with Coyle's widow nigh information technology. Coyle had died in 1996. Before Simmons died in 2010, Weisman had spoken to him and his wife, who, Weisman said, "thanked me for setting the record straight. She said, 'You lot know Chet could never accept told that story himself.' "

The tape of the Game 6 telecast was non fully prepare, though. A whopper of a fable remained.

*****

The fable goes like this: Gerard defenseless ane of the nearly famous images in sports telly history, the one that allegedly "invented" the reaction shot, only because a rat the size of a cat was at his feet and Gerard was as well afraid to swing his camera to follow the flight of Fisk's home run ball. The story of this happy accident has been told time and fourth dimension again over 40 years.

But when Leggett visited Coyle at his New Jersey home the week afterwards the World Series, Coyle said only that Gerard "was fighting off rats in there most of the night. He had to keep one eye on the game and another out for rats. When Fisk hit the ball toward leftfield, nobody could tell if it would be off-white or foul, and then it was bang-up for us when one of our cameras got a proficient shot of it hitting the pole." Coyle did not say that Gerard had broken from The Bible to stay on Fisk because a rat appeared. Only over subsequent years, and with increased fervor, the director and the cameraman delighted in telling that tale.

"Flash, wink," said Weisman. "First it was a rat by his pes, then afterward a couple of years it was a rat on his shoulder, then it was a rat nether his hat eating a ham sandwich.... Only one of the rumors and the wives' tales and the exaggerations that came out of the game."

If Gerard really was supposed to stay on the activity, how could a camera inside the leftfield wall follow the flying of a baseball hitting the leftfield foul pole? And the shot from the loftier third camera of Fisk jumping—Coyle'southward offset replay—wasn't that a reaction shot? And going all the way back to Coyle'due south get-go World Series, in 1947, wasn't the shot of Joe DiMaggio kick the dirt later on getting robbed by Al Gionfriddo a reaction shot?

"I don't think yous can say it was the first [reaction shot]," Weisman said of the Fisk image. "I think yous can say it popularized it. It made information technology more than important to show people'south emotions and reactions away from the ball. That was raw emotion from Fisk. It made yous smile. Information technology was inarguable later on that about showing the thrill of victory."

*****

Anderson felt terrible subsequently Game 6. He thought his pitching moves had doomed his club. He saw Rose and Johnny Bench in that tiny visitors' clubhouse and barked, "Big Red Machine, my donkey."

"Sparky, relax," Rose said. "Did y'all meet that celebration they had? Nosotros got 'em right where nosotros want them. We just played in ane of the greatest games ever. Don't worry. We'll win tomorrow."

The Reds did win Game 7 the next nighttime. It was the highest-rated telecast to date, and has been exceeded only by Game 6 of the 1980 Series. "More surprising than the huge numbers for the seventh game is the fact that they occurred during prime evening hours, when viewers supposedly adopt state of affairs comedies, dramatic series and variety shows to sports," Leggett wrote. "Sponsors, promoters and the networks will have to rethink their former assumptions about baseball and prime-time sports telecasts."

Kuhn crowed in his book that Fisk'due south home run would not accept had nearly the same bear upon if he had hit it at 4:30 on a weekday afternoon, as the pressmen would have had it. Said Weisman, "I guarantee the ratings for Game half dozen grew the longer that game went on. If that game in 1975 was a blowout or didn't go extra innings, who knows what would have happened. Just it actually saved baseball. Madison Artery bought in."

There was no going dorsum. NBC asked Kuhn for a fourth night game in the next Earth Series. The commissioner granted it "on an experimental basis," scheduling Game ii as the first weekend night game in Series history. It was held in frigid conditions in Cincinnati. Comically, Kuhn watched the game without an overcoat but with long johns underneath his suit. Before the game, Yogi Berra, a Yankees coach, snapped, "What are we playin' for? The title of Nielsen?" By 1985, the Earth Serial had get an all-prime number-time event.

Game 6 in 1975 ignited a revival of baseball that would last more than than a decade, something Anderson seemed to sympathize even every bit he left Fenway later on Game seven. "Nosotros didn't win the Earth Series," the skipper said. "Baseball did."

Omnipresence rose 5% in 1976, Mon Dark Baseball ratings went upward 19% and All-Star Game ratings went up 28%. The next tv set contract, signed in 1979, doubled baseball'southward almanac take from the networks. The 10 highest-rated World Series all occurred in the window of 1971–86.

(The catamenia of remarkable growth was likewise ignited by another upshot, two months afterwards Fisk hit his home run: a ruling that ended baseball game's reserve clause and paved the way for free bureau. The average salary in 1975 was $45,000. By '78, it was $100,000.)

Televised sports quickly became not only a prime number-fourth dimension fixture only also an all-the-fourth dimension fixture. Four years after the 1975 World Series, Simmons left NBC to help launch and lead ESPN, taking Connal with him. Weisman went on to become ane of the greatest sports producers in the industry and now oversees MSNBC'due south Morning Joe. Stockton was in demand after the '75 Serial: NBC hired him to telephone call NFL games, and two years later he moved to CBS, where he became the network's lead basketball broadcaster. Xl years afterward, he tin can hardly walk through an airdrome without someone recognizing him and proverb, "If information technology stays off-white...."

"I've been blessed to call some great events over the years," Stockton said. "That remains No. ane. Nix has ever surpassed it."

In 1998, TV Guide ranked the Fisk home run as the height moment in the history of televised sports. Since so the reaction shot has often replaced the action shot as how we best remember a peachy moment: Gibson pumping his fist every bit he rounds the bases, Carter leaping well-nigh commencement base of operations, Gonzalez with his arms raised, Freese spiking his helmet betwixt his legs, Bautista flipping his bat....

Coyle fabricated sure it would exist that way. After the 1975 Series, he made a rare amendment to Harry's Bible: Photographic camera operators heretofore were instructed to stay on their shots for another five seconds afterwards the play ended. "After this game," Weisman said, "information technology went from the Erstwhile Testament to the New Testament. The edict was to stay for the reaction."

The image of Fisk waving the ball off-white instantly became more than powerful than the dwelling house run itself. Modify that dark was as clear as the bells of St. Luke's. We would never look at sports on TV the same way again.

Source: https://www.si.com/mlb/2015/10/21/game-changer-carlton-fisk-nbc-1975-world-series

Posted by: williamscollas.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Many Tv Cameras Were Used At A Mlb Game In1970"

Post a Comment